I was 8 years old when my twin brother had signed up to play youth football. I was not allowed to play, out of fear I might get hurt because I was a girl. Up until that moment, my brother and I had been playing soccer together on a co-ed team since we were five. Both of us were naturally athletic and had great coordination and dexterity. Sports came easily. I held my own with the boys, and was better than most.

As for football, I had already been playing tackle with my brothers and their friends on the street, in backyards and on rock-filled school playground lots. But now my parents were worried about me getting hurt? It didn’t add up. Still, no matter how much I protested or how much my brother advocated on my behalf, they never changed their minds. I was forced to sit in the stands and watch from afar, and my football-loving heart ached with envy with every snap of the ball.

A few years later, the head coach of my indoor soccer team pulled me aside after a game. I was the only girl on the team and we had all been playing together for a while. As my coach knelt gently in front of me and put his hands on my shoulders, I saw it in his eyes even before he said the words. They went something like, I wouldn’t be able to play with the team any more, because it was getting too rough. I stopped listening after that. The all-too-familiar feeling of being told I couldn’t do something because I was a girl had settled into my gut, and my eyes were wet. I didn’t say a word during the car ride home, even when my brother tried to console me. It wasn’t his fault, of course. But he couldn’t understand. He’d never understand.

In writing Hail Mary and listening to players describe how it felt to finally get to play a sport that everyone told them they couldn’t and shouldn’t be playing, I reconnected with my 8-year-old self. I knew how they felt and could imagine how rewarding it was for them to take the football field on game day, to put on their uniforms and to play in front of a crowd. They played because they loved the game. And they played for all the young girls out there who, like me, were told no, this sport isn’t for you.

***

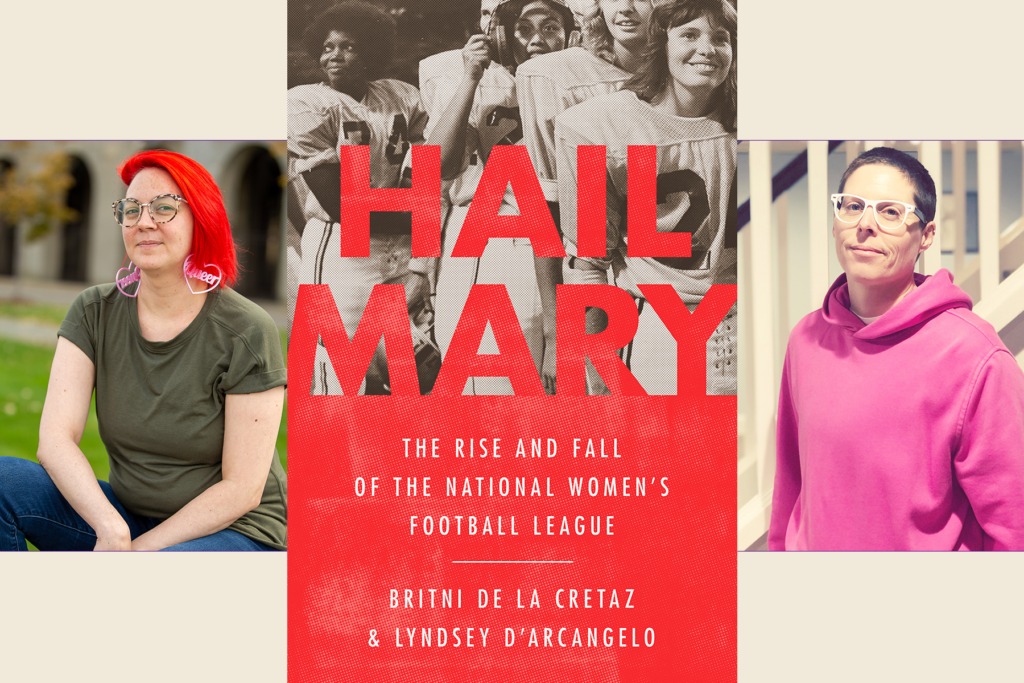

This article has been excerpted from Chapter 5 (“The Troopers’ Reign Begins”) of Hail Mary: The Rise and Fall of the National Women’s Football League by Britni de la Cretaz and Lyndsey D’Arcangelo. Copyright © 2021. Available from Bold Type Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

“I did not pose for that,” Gail Dearie, now eighty, said of the iconic photo. “We were having a scrimmage at practice. I had just stood up after the huddle. I was thinking about my route for a play. And a [European] photographer snapped that picture. Apparently, she liked what she got. She thought it was worth trying to send it to Life magazine. The picture really took off. Now, we say ‘it went viral.’ A lot of things happened as a result of that picture.”

In June 1972, Life published a photo spread with a short article about a new women’s football team—the New York Fillies. (The Fillies, however, appeared without the support or blessing of Sid Friedman. They were not under his umbrella of teams, and were owned by someone else.) Life’s writeup of the Fillies was only the second such feature about women’s football in the magazine’s history.

Twenty-nine-year-old Dearie from Red Bank, New Jersey, was one of the players featured in the photos, and one photo in particular stood out from the rest. Dearie is clad in a grass-and-dirt-stained white jersey with the number 84 on the front, her long blond hair falling out of her large gold helmet and down onto her shoulders, and her high cheekbones and full lips distinguishable underneath the thick gray face mask. The full-page photo contrasted beauty and brawn, and it attracted national attention.

In spring of that year, before Dearie became the most recognizable Fillie on the roster thanks to the Life magazine photos, she was working in New York as a go-see model in commercial print media when her husband showed her a wanted ad in a national paper looking for women to join a new professional football team. Dearie was intrigued and decided to see what it was all about. Her main reason for going, she said, was to “put away a slap-in-the-face kind of attitude that some people have about athletic ability and women—not being able to use it fully because it didn’t seem feminine.”

She wasn’t the only one. Nancy Berardino, a seventeen-year-old from Far Rockaway, had also seen the advertisement. Her twenty-four-year old sister, Lynda, wanted to try out for the team as well. Dearie, the Berardino sisters, and Dearie’s friend Carol Brown were among the hundred or so women who showed up to the Fillies callout.

“Some of them had never played football before. Some didn’t know very much about the technicalities of the game,” Brown told womenSports magazine in 1974. “But every woman there wanted to be a professional football player.” The women who showed up for the tryout did so with the hope of proving wrong anyone who didn’t believe they could play football, and also because they loved sports and wanted to take advantage of the opportunity to play.

Dearie stood tall above the crowd, not just for her athleticism but also because of her beauty. In truth, Dearie was the perfect person to dispel the myth that a woman couldn’t be both a good athlete and feminine at the same time. While she turned heads wherever she went in the city, it often frustrated her that her looks were the main thing some people chose to focus on. Like all women, there was much more to Dearie than her outward appearance. She was a mother of two, a wife, a devout Christian, a model, and a part-time college student. She was also an athlete.

When Dearie finally got the opportunity to step on the football field on the day of football tryouts, she turned heads for a different reason—her height at five feet eight inches, athletic ability, and strength made her the perfect wide receiver or tight end. “It was legitimate,” Dearie said, recalling the tryout. “They weren’t making fun of women, if you know what I mean.”

Dearie and Brown made the team, along with forty other women from the surrounding New York City area, ranging in age from sixteen to forty years old. They were promised twenty-five dollars per game, fully funded by Fillies owner James Eagan: a cocky New York City attorney.

Eagan started the New York Fillies because he believed it was a solid monetary investment, and was hoping to make some extra cash on the side. It was certainly not because he wanted to help elevate women’s football. For him it was a business venture, nothing more. He didn’t care about the women’s dreams or aspirations on the gridiron. To Eagan, the women were simply a means to an end.

“They drew 6,000 at three dollars a head in Erie,” the young and slick Eagan told the Philadelphia Daily News before the Fillies debut game. “Can you imagine that kind of crowd in Erie, Pa.?”

Eagan knew very little about football and the game itself, and spent time at practices familiarizing himself with the rules. He brought in Bill Bryant, a former semipro football player, to be the head coach of the Fillies and he hired additional assistant coaches to handle all the technical stuff, like training the team and getting them ready to play their first game in front of what Eagan anticipated to be a huge crowd.

Bryant did his best to teach the Fillies plays on the offensive and defensive side of the ball. “I’m trying to teach these girls the fundamentals,” he told the Daily News. “You have to start at the beginning and some learn quicker than others. These girls are a lot more serious than you think. They’re playing to win.” But when Eagan, who was quick to shave expenses, decided not to purchase medical insurance for his players, all four coaches quit the team in “protest and disgust” the night before their first game.

The fact that the women were willing to play without insurance coverage indicates how badly they wanted to be out there, how deeply they understood what a rare opportunity they had.

***

Baseball may be America’s pastime, but football is Ohio’s. On Friday nights in the early twentieth century, the mill towns would shut down for football games. As early as 1922, Ohio State University built a sixty-six-thousand-seat stadium, a shrine of sorts, which was at the time the largest poured-concrete structure in the world. Before there was the NFL, there was the Ohio League, a loose alliance of independent, semipro teams—not all that different from the women’s football teams under Friedman—from cities including Toledo, Cleveland, and Youngstown. The Pro Football Hall of Fame is located in Canton, Ohio, the same place the NFL was born. In Ohio, parents put their boys in the sport from the time they are in elementary school.

Throughout the entire United States, too, football is almost like a religion. Some people go to church on Sundays to say their Hail Marys; others sit around the television and turn on the football game, hoping to see a Hail Mary of a different sort. Americans worship their teams like they do their gods, and everything else ceases to matter while the game is on. Game day is a holiday, a holy day.

For girls growing up in this culture, forced to always be the spectator—in Ohio and Texas, yes, but also anywhere in America—it was only natural that there would be an overwhelming feeling of missing out. While there may have been other sports that were becoming more accessible to girls in the seventies, like rec league basketball or softball, those sports were consolation prizes. As much as the girls loved playing them, in Ohio at least, football was the sport: lionized by their friends and family, and always off-limits to the girls. If they were lucky, they could scrimmage with their brothers or the neighborhood boys, but that was as close to tasting organized football as they ever thought they could get. The reality of putting on pads and helmets and jogging out onto a real football field, with fans in the stands cheering them on, was one that existed only in their wildest daydreams. Even though girls were gaining ground in other sports leading up to and after the passage of Title IX, they were still shut out of football. And, in Ohio, this meant shutting girls out of the sport that mattered most.

But that didn’t make football matter any less. Just how much football mattered—to these girls, in this state—was evident in the Troopers’ first tryout.

***

More than eighty women showed up to try out for the Troopers in 1970. But Stout only wanted twenty-two: the best athletes, the most committed players, who would put in the work he knew would be required to turn a bunch of rookies into champions. His players practiced five nights per week in Colony Field, a weed-covered patch of grass hidden between US 23 and a rundown section of Toledo.

There were plenty of teams whose coaches believed they were more than a gimmick and viewed them as real athletes. Bill Stout, however, would be the first to go to bat for his players and help them create and envision a league that took them as seriously as they took themselves. He would also continue the tradition of women’s football in the Rust Belt city of Toledo, located near the Michigan border and on the shore of Lake Erie.

Stout was a former All-City noseguard for DeVilbiss High School in Toledo whose pro football dreams had crumbled. Before he began coaching the Troopers, he was a struggling factory worker with a gambling problem. He felt like he was out of options, so he turned to coaching women’s football—which he didn’t take seriously until he saw the dedication and determination of his charges. He was a white man in his late twenties who carried his weight in his belly and wore mutton chops down his cheeks. He almost exclusively wore that very 1970s brand of athletic shorts and a polo shirt, a whistle draped around his neck.

Stout enlisted Carl Hamilton to coach the Troopers defense. Hamilton, a stocky Black man who wore a dour expression in photos but had a knack for getting the best out of his players, had played football at Bowling Green University. A high school teammate of Stout’s named Jim Wright, a white man with a full head of brown hair parted to the side, a crooked smile, and a dimple in his right cheek, came on board as assistant coach. The team played most of their home games at Waite High School, a large brick building near downtown. Another woman who would go on to blaze trails for the women who came after her also has a Waite connection—Toledo native Gloria Steinem attended in the late 1940s.

In the Troopers’ first season in 1971, there weren’t many options when it came to opponents in Friedman’s collection of teams. They played only three games that year, one against the Buffalo All-Stars and two against the Cleveland Daredevils. They won all three by large margins. Almost immediately, Stout internalized the narrative that this was a team of winners, that they were champions, and he began to parrot it until his players believed it, too. It didn’t matter that they’d hardly had any competition: his team was the best, and by asserting it he would make it true. Even so, privately, he harbored some doubts as to how successful his team could be. “The brand of football wasn’t that good when we started,” he later told the Toledo Blade. “I never thought people would pay a second time to see us play.”

***

The 1972 season established the Troopers’ core identity: it was the year Linda Jefferson, the greatest halfback in the league, joined their team, giving the offense a jolt. The player—called a “bionic femme,” in an article comparing her to O. J. Simpson of the NFL’s Buffalo Bills—rushed for 1,179 yards in her first season with the Troopers. She averaged an astonishing 41 yards per touchdown run. Meanwhile, the team’s defense, known as the Green Machine, really took shape under defensive coach Hamilton. Now, they were stopping opposing teams in their tracks. “The defensive animal squad is Carl’s pride,” read a poem from their yearbook, which also indicated there’d be repercussions for any points the defense allowed: “Let them score—it means leg lifts and you wish you’d have died.”

Midway through the season the Troopers also acquired Gloria Jimenez, a Mexican American hairdresser who joined the team at the urging of her friend. The two were “young and rambunctious and didn’t have enough to do,” so they decided to go out for a football team. Jimenez had virtually no experience with organized sports at the time. What she did have, however, was five brothers and a lot of enthusiasm. “My dad always used to say, ‘I’ve got five sons and my daughter plays football.’ . . . I had more trophies than all my brothers put together.”

Over the course of her time as a Trooper, Jimenez would be a true gadget player, a jill-of-all-trades who could slide in wherever she was needed. She played defensive end, defensive tackle, middle linebacker, offensive tackle, a little bit of fullback, and she was also the kicker. Jimenez played both ways, she played special teams, she did it all. She essentially never came off the field during a game.

When they went 8–0 in their second season in 1972, the Troopers’ team yearbook declared them “NUMBER ONE” and “the best damn team in the league.” And they were, by a long shot. In games against the Cleveland Daredevils, the Detroit Demons, the Buffalo All-Stars, and the New York Fillies, the Troopers scored 298 points, while their opponents scored just 32. Five of their games were shutouts. Bill Stout got what he wanted; he really was coaching a team of champions.

At least, that was how they rounded out their first two seasons. But their first game of the new 1973 season would be against a new team, the Dallas Bluebonnets (some historical records put this game in the Troopers’ 1972 season, citing that season’s record as 9–0). When the Troopers got down to Dallas and exited their bus, they walked into a real stadium. It felt as if women’s football might just be on an upswing. Goodbye, high school football field, hello home of the Dallas Cowboys.