When San Diego's home match against the Washington Spirit ended in a 0-0 draw on June 22nd, the NWSL officially pressed pause on the regular season, entering an extended summer break as international tournaments kicked off around the world.

And while the US club league has dimmed its lights before — most recently during the 2024 Paris Olympics — this is the first year it's ever stopped play to accommodate major regional competitions like Copa América, WAFCON, and UEFA Women's Euro 2025.

Why the new approach? The league's global presence has never been stronger. And that's not just because high-profile players like Naomi Girma and Crystal Dunn swapped their NWSL jerseys for European kits earlier this year. It goes the other way, too. Once an assumed stronghold for homegrown talent, the NWSL has diversified its ranks, with top players heading overseas this window.

US broadcasters buy into growing Euros interest

No event has showcased this shift greater than the European Championship. The tournament was once siloed away from the average Stateside soccer fan. But this year, 18 NWSL players representing 12 countries are Switzerland-bound — three-times the number playing in England just three years ago.

And fans are ready to dig in. The 2025 Euros will be the most accessible in history, with FOX Sports recently doubling down on broadcasting the competition in the US.

The network has committed to 31 matches, including 19 games on linear TV and every knockout round match. It will also provide pre- and post-game analysis, aiming to develop a major market player while riding out the sport's popularity boom.

With increased visibility and plenty of familiar faces, NWSL fans are set to become Euro 2025's prime audience. And for players, showcasing the league's impact shapes the perception of football in the US, allowing the NWSL the opportunity to strengthen its reputation despite never taking the pitch this July.

Euros stars say perceptions of the NWSL are shifting

Only one NWSL player featured on England's 2022 Euros-winning roster. That was Houston forward-turned-defender Rachel Daly, before she returned to the WSL and retired from international play.

That number tripled in 2025, after Gotham FC defender Jess Carter, Spirit defender Esme Morgan, and Pride goalkeeper Anna Moorhouse were called up to the Lionesses's title defense in Switzerland.

It's not Carter's first Euros, but this will be the first year she joins from an NWSL team. An England mainstay since her 2017 senior debut, she said she never felt like a move to the US would jeopardize her national team standing. Just so long as her performance stayed consistent.

"People were probably apprehensive about coming here before, because it's so far away from your family and friends," Carter told Just Women's Sports. "But also because the NWSL was traditionally known as just a transitional league. And to a lot of people in Europe, it wasn't technical enough."

Carter isn't alone in her assessment. Both Morgan and Moorhouse told JWS they were familiar with the NWSL's reputation as a "kick and run" league. Though that stereotype didn't match their experiences on the ground.

"Most [NWSL] teams are trying to play possession-based football, albeit a little more direct than Europe," Morgan said. "I think that's far more exciting to be a part of, and also more challenging as a defender because there are such fast transitions."

"The league is changing here in the US," echoed Carter, who departed Chelsea for Gotham in 2024. "It's becoming more technical."

NWSL play helped Morgan secure her spot with England

That hybrid style — plus more starting opportunities — have bolstered Morgan's status with England. Coach Sarina Wiegman already knew the Manchester City product as a powerful line-breaker on the ball. And her ability to wear down the low block while holding the lion's share of possession has only improved.

"I felt confident coming here," she continued. "As long as I continued to work on the things that I wanted to improve, and every weekend was putting in good performances for the Spirit, that would be enough to put me in the running for selection."

The NWSL's speed has also elevated her play. "[Wiegman] has spoken to me the last couple of times about being really pleased with what I've been able to do, in terms of being a little bit more aggressive, proactive, physical in my duels, and winning aerial balls," she said. "I've developed so much in that space since playing in America."

Both Morgan and Carter competed with England at the 2023 World Cup, 30-year-old Moorehouse is gearing up for her first major tournament with the national team. And coming from an Orlando side stacked with international talent — namely Brazil legend Marta and Zambia superstar Barbra Banda, among others — the goalie credited her NWSL team for keeping her on her toes every day.

"Marta humbles me on a daily basis, I'm not gonna lie," she laughed. "To see that day in-day out, it's only for the better. It's only going to improve my game."

Summer NWSL schedule benefits Euros-bound players

As coveted national team roster spots reflect both consistency and form, NWSL players have a quiet advantage. Thanks to the summer NWSL schedule, they're guaranteed to be completely match-fit going into any major tournament.

That the NWSL runs opposite to the more traditional fall-to-spring European setup has sometimes been a point of tension overseas. This was especially true in past years, when the league did not suspend regular-season play for more than a weekend or two during longer international windows. That practice forced previous Euros competitors to choose between club and country.

This year, however, players view the cross-conditioning to be as much of an asset as an anticipated challenge when they return to finish out the season.

"I spoke to quite a few of the US girls in the past about the fact that the summer schedule might have helped their performance in international tournaments," said Morgan, pointing out the NWSL-heavy USWNT's major tournament success.

"I feel like I'm peaking at the right time, going into the tournament in midseason," echoed Moorhouse, who is set to serve as backup to Chelsea goalkeeper and presumptive England starter Hannah Hampton.

Learning to balance club and country

Still, there are downsides. It's not always easy to travel in and out of market ahead of a big international opportunity, but each player finds their own way to stay on top of whichever task is in front of them, whether at home or abroad.

Sometimes that divide between club and country is literal. "We have a [NWSL] team app where we have communication," Gotham and Germany goalkeeper Ann-Katrin Berger told media after her Euros call-up. "I was like, 'Look, if you need something, you have to text me on WhatsApp. Because this app is not working for me when I'm at the international break, and the same way around.'"

For Carter, the NWSL's schedule helps her compartmentalize, keeping her laser-focused on both individual and team goals.

"I'm someone that either is all in or all off," she explained. "I've got to make sure that I'm still eating right, training right, when all I want to do is sit by the beach and have an ice cream."

"I want fans to fall in love with women's football even more"

Carter and Berger aren't the only Gotham standouts packing their passports this month. Star forward Esther González is also committed to play for the always-dangerous Spanish national team. Fellow forward Jéssica Silva will represent Portugal and recent signing Josefine Hasbo is set to join Denmark. And the excitement is palpable, both on and off the pitch.

"It's really great to see that our fans get to support us even whilst we're not at Gotham. Because they're invested in us as people, not just Gotham," says Carter. "I want fans to fall in love with women's football even more, regardless of where it's being played."

As for Morgan, she could be battling against the Spirit's newest signing, Italy's Sofia Cantore. The rest of their teammates will definitely be watching from home — along with a very special guest.

Before Morgan left, her teammates assured her they would be up in the morning cheering her on. "And mak[ing] my kitten watch too, which is very cute," she added.

She said she likes imagining NWSL fans following their favorite club players through the tournament, staying engaged in the game even as the league takes a break.

Encouraging NWSL fans to watch the 2025 Euros

Moorhouse echoed Morgan's hope that the Euros will allow US fans to continue weaving women's football into their lives during the downtime.

"In the US, when I get up on a Saturday morning, all the games are on," she said, referencing the time change. "To me, that's so cool. I'm eating my breakfast, drinking my coffee, and I've just got football on the telly."

"Go and get your breakfast," she urged. "Get your pancakes. And watch some good football."

Sophia Smith isn't much of a gamer.

"It just does not come naturally to me," the Portland Thorns and USWNT forward tells Just Women's Sports with a laugh. "I think with more practice, I could get good."

Whatever skills Smith may lack on the virtual pitch are made up in full by her talent on the actual one. And that talent has ironically earned her an outsized on-screen role in the popular soccer video game EA Sports FC.

Earlier this week, the 24-year-old earned her second-straight spot on EA Sport's Team of the Year. The honor that places her alongside international heavyweights like Barcelona's Aitana Bonmati, Chelsea's Lauren James, and Lyon's Wendie Renard.

While gaming might not have been front of mind when Smith won Olympic gold in Paris last summer, she has noticed how FC 25 has become an essential way for soccer fans to get to know their favorite players. The franchise only started fully integrating NWSL teams in 2023, but Smith's rise to in-game prominence was swift.

Her avatar is regularly featured in national TV commercials, scoring in both a Thorns and a USWNT jersey alongside men's soccer stars like Real Madrid's Jude Bellingham. It might be just a video game, but FC 25 feels increasingly like one of the few platforms that views both sides of the sport as having equal potential.

The phenomenon is not lost on Smith. She says that from time to time fans will recognize her not from the Olympics or an NWSL championship appearance, but from the video game. "When people have the ability to play with women in a game that they've played all their life, it opens a whole new door for us," she says.

"It's so great for women in sports, because it shows that we also deserve to be in a game," she continues. "We also deserve to have that platform, to have our names out there at the same level as the men."

EA FC levels the playing field

While the EA FC 25 Team of the Year is voted on by fans, the breadth of leagues in this year's lineup also calms some of the debates currently raging within the women's side. It's no secret that NWSL players sometimes have trouble gaining traction in top European awards. This is a tension that Smith herself has faced before her US national team breakout.

"I do think the NWSL isn't recognized enough," says Smith. "People have a lot of opinions on it, maybe people who don't even watch any games. That can be frustrating because it's a very challenging league to play in — every game is competitive."

To prove her point, she references the time it's taken for her USWNT teammate and fellow Stanford alum Naomi Girma to gain recognition on the international stage. If there were any player she could add to EA FC's Team of the Year, she adds, it'd be the San Diego Wave center-back — "and not just because she's my best friend." The growing global market for NWSL-based players like Girma and Smith likely won't silence critics promoting European-style football over American. But Smith sees differences across leagues as an asset for a player, not a problem.

"Either league could be good for any player for a number of reasons," she explains. "You can learn something in Europe that you can't learn here, and vice-versa. That's why players go back and forth."

"I believe that every league that exists can be challenging in its own way, and we're all just trying to figure it out," she continues. "FC having women in the game — women from the NWSL and European leagues — just puts us all as equals as we should be. It allows you to determine someone's game based off someone's game, not if they play in Europe or the NWSL."

Focusing on USWNT growth in 2025

Smith's game speaks for itself. Coming off a disappointing 2023 World Cup, the forward scored three goals and registered two assists during the USWNT's Olympic run, leading the team to their first major tournament trophy since 2019. Her club contributions were similarly impressive. She scored 12 regular-season goals alongside six assists despite Portland's failure to make it past the 2024 quarterfinals.

But the year took a toll, and Smith says that prioritizing rest has been essential to preparing herself for everything 2025 has to offer.

"I feel like this offseason was very much needed for me," she says. "While it was a great year, it was a long year — we just gave everything 110%, 24/7, so when we got to the offseason, it kind of just smacked us in the face."

Smith says she's physically bouncing back after a lingering ankle injury limited her playing time in the later half of 2024. "Most offseasons I'll take a few weeks and I'll start training," she says. "This offseason I took a little longer. I knew that in order to start this next year off right, I needed to give my body what it needed while I could."

With no major US tournaments set for 2025, Smith is looking forward to seeing the national team continue to gel and evolve. She's a big believer in USWNT manager Emma Hayes's "If it's not broken, break it" ethos. It makes her excited to push herself and her team to take things to the next level.

Bringing the EA FC Team of the Year energy back to Portland

Smith also has work to do in the NWSL. She's rejoining a Portland club that saw multiple legends of the game step away after 2024's uncharacteristic sixth-place finish. As a leader, she wants to see the Thorns back at the top of the table. And she hopes to carry on the legacy of retired stars like Christine Sinclair, Becky Sauerbrunn, and Meghan Klingenberg.

"Since I arrived in Portland, every year there's been change. I'm just used to it at this point," she says. "The best thing we can do as players is stick together, really just show up for each other every day. And work towards the same goal, which is to win."

"It's easier said than done," she admits. "I'm used to being one of the younger players on the team. I still am, but I have more experience. I feel like I can be a leader in a different way."

With 2024's triumphs behind her, Smith views the new year as an opportunity to improve without the intense pressure of a major tournament. As always, the goal comes down to one simple thing: growth.

"I'm not the loudest person," she says. "But I can lead by example and show up every day, trying to be the best version of myself and helping those around me get better, too."

Making connections on and off the screen

One thing Smith can guarantee is that she'll continue to connect with fans. That goes whether it's signing autographs after a match or finding the back of the net in EA FC 25.

"It wasn't that long ago that I was that little kid, watching people I grew up looking up to," she remembers. "If they took a minute out of their day to say hi or to sign something, that stuff means a lot."

"So I try to be that person for people. If I can do that through FC, if I can do that in real life, I always take the opportunity."

In the UK, the path toward becoming a professional soccer player starts early.

Kids in the US usually start out with local or travel clubs before moving to a high school team and then maybe playing in college before going pro. And recently, a small but growing number of teenage players are opting to sign contracts with the NWSL before they’ve even finished school.

But across the pond in the UK, a promising footballer’s road to stardom can start as young as five years old. The academy system was established to guide aspiring young players as they work towards an adult contract, with professional clubs like Arsenal, Liverpool, West Ham, Chelsea, and others supplying their youth programs with full-time coaches, training facilities, and a match calendar. Then at 18, the senior club either offers the player a pro deal or releases them to pursue a spot on another team’s roster.

The goal has always been to nurture and sustain homegrown talent, with academies around the league producing WSL and England national team icons like Leah Williamson, Lauren James, Lotte Wubben-Moy, Lauren Hemp, Chloe Kelly, and Mary Earps. And now more than ever, it’s something big league teams are focused on given the women’s game’s meteoric post-Euros rise in the UK.

Of course, academy life isn’t just afterschool practice and weekend fixtures at the training grounds. When senior clubs travel for international friendlies, they’ll often invite a few academy players to tag along. It’s a way to give the young players some exposure, bonding time with the team, and minutes on the field, all while the coaching staff has the opportunity to evaluate their progress and see how they gel with the club.

That was the case for Michelle Agyemang and Vivienne Lia, two up-and-coming academy products who joined Arsenal FC on their recent USA tour. 18-year-old Agyemang recently graduated from Arsenal’s academy, signing her first pro contract with the team this past May after debuting in November 2022 at the age of 16. 17-year-old Lia is still finishing school and academy training, having taken the field with the senior club for the first time in February 2024.

Last week, JWS spoke to the England U19 standouts in Washington, DC ahead of Arsenal’s friendly with crosstown rivals Chelsea to learn more about their journeys from childhood Gooners to academy superstars and beyond.

How's the trip going so far?

Michelle Agyemang: So far good. I think it's been good to go out and see the monuments and stuff, and obviously training. It's been nice to be around everyone as well.

Viv, this is your second team trip after Arsenal’s Australia exhibition in May. How are you finding it?

Vivienne Lia: It's great. Australia was more hectic with the fans, but over here it's been relaxed. But it's also been more dense — because it's pre-season, we've been working a lot more than we did in our postseason trip.

How old were each of you when you signed with Arsenal Academy?

MA: I was six.

VL: I was 14.

I know Arsenal has recently moved away from academy trials and now uses a talent identification team to recruit young players, but what was the process like when you joined?

MA: At the time, you just apply on a website, come in for a massive trial with about 30 girls, do a bit of training, and then if you're successful, you go to a second round with less girls. And that's it: Two sessions and then they send you an email or a letter. It's quite simple really.

VL: Mine was quite similar. There was a trial system: one and two trials. At the first one there were quite a lot of girls and then it cut it off a bit. From there, you get an email whether you got in or not. Now it's changed where they don't have open trials — you come in for training sessions instead.

Did your parents sign you up?

MA: I was playing for a local boys team and my dad was like, "Oh, might as well just sign her up." So he did, for a few different teams. And then we literally just rocked up to [a pitch] not too far from Colney for a little training session.

Do you remember that day?

MA: I do quite well. To be fair, we got lost on the way. We went to, I think it was a little farm instead of the training pitch. And then I remember my dad, he kind of pranked me a bit. He was like, "Oh yeah, sorry Michelle, you didn't get in." Then he actually brings out the letter. So it was really cute — a really good day.

If you were raised in the US, do you think you would have tried to turn pro at a young age or opt for the college route?

VL: I think probably the school route, because you want to get a firm foundation of education first. Because your career is not guaranteed at whatever age — you can get an injury, God forbid, and of course that's part of the game.

MA: I'd say the same. It’s also the experience of college — so many of my friends have gone through college and it just looks like good fun, obviously alongside football. You miss that if you go straight to pro. Getting school alongside football is something we don't get in England, so I think that'd be a really good balance to have between the two.

When you're in the academy, how much time are you devoting to soccer?

MA: I'd spend as much time as I could on both. So as soon as I finished school, I'm straight into the car, changing in the car, eating in the car, doing homework in the car, on the way to training. And then on the way back, I slept. It was an endless cycle but that was the only thing I knew.

VL: When you're younger, it's still a mix of it being a hobby but still your passion. But then as you get older — when it becomes more jam-packed, more serious — you have to try and find a balance between both. In England the systems are split, so you still have to go to school, but you also have to go to training. For me now, I go into school two, three times a week and training as well, so it’s about finding a good balance.

So you’re both lifelong Gooners — was Arsenal always the dream?

VL: Yeah, 100%. That was the dream for me. Of course, I grew up in North London — everyone's either Arsenal, Tottenham, Chelsea, or you got the odd northern team they support. Everyone wants to play for their local club, their childhood club. It was always a dream of mine to play for Arsenal and to make history at this club.

When you were younger, did you see women’s football as a viable career path?

MA: Absolutely not, no. My mum was saying to me the other day that she just thought I'd just go to Arsenal to do a few training sessions and then come back home. But the development of the game has been so fast in recent years. So I never really saw it as a career until maybe under-10s, -12s when it actually started to get much bigger as a game. At the beginning, I don’t think I had a real plan for football. But things change, and here we are.

Was the experience the same for you, Viv, seeing as you joined the academy a bit later?

VL: Different actually. I always wanted to be a footballer — or at least an athlete. It was either tennis, track, or football for me. But I always had more of a love for football, so I was like, "Okay, if I don't become a footballer, I'll be a tennis player instead." Like, "I'll be in sport."

Football was always what I wanted to do, but I wasn't completely sure it was possible. But as a kid you're like, "Oh yeah, it'll be possible. I can do anything." So I didn't really think of that side of it until I got older I was like, "Oh, this is actually something that I can do as a profession."

How has your game changed as you've gotten more time at the senior level?

MA: At Arsenal, the passing, the movement — everything is so crisp. It's a shock at first but you adapt. For my game, I’ve added more technical bits: passing, moving, working together as a team. As a kid, you want to go run and score 10 goals, but you obviously can't do that here. So working with teammates, moving the ball, moving myself to help other players — that's a big part of my game that I've improved here.

VL: The details are so important at this top level. At youth level, you can get away with not pressing as hard or not recovering as quick, but [in senior club games] you'll get punished for that. It makes sure that you're always working to the best of your ability, but also it switches you on mentally. You have to keep attuned to how quick the game is or spot different triggers — that's the main difference between senior football and youth football.

What is your favorite Arsenal memory?

VL: It was the season before last season, the Champions League game against Bayern Munich at home when Frida Maanum scored top bins. I was ball-girling for that and I had the perfect view of it. I was like, "This is the best goal I've ever witnessed in my life." Being an Arsenal fan, [knowing] the context of that game, I was like, "Wow, this is incredible."

MA: That's a good one. I’ll go for two seasons ago when we played Wolfsburg at home in the [Champions League] semi-final. I think it was two-two going into the second leg and then for me, coming on very late in the game — a Champions League debut — that was a massive moment. Just the atmosphere, 62,000 fans, everything.

After playing the Washington Spirit earlier this week, how do you find the NWSL compares to the WSL? Is there a different flow to the game? A different approach?

MA: We always associate America with athleticism, so the transition element was so fast at every point in the game, from the first minute to the last. And the atmosphere was very interesting as well. You got the fans hyping up a corner kick — like, "Get up and cheer. It's a corner kick!" I've never seen that in my life, never ever seen that, but it’s nice as well. I liked it.

VL: Yeah, the game was very fast-paced. But it was really on runs, their wide players just bombing it forward. The physical level of the game is top. As you said, the rest of the world associates America with athleticism — powerful, fast, physical. That was something that I thought of straight away, like it's less technical but still at a high level.

Where do you guys see yourself in five years?

MA: Right here.

Right in this room?

MA: Yeah. (laughs)

VL: In DC?

MA: Yeah, in DC. It would be awesome coming back. Imagine.

VL: I'll say the same: At Arsenal, establishing myself in the senior game and really showing what I'm about. And that's it — that's a good one.

Madison Keys was just 16 when she featured in her first US Open, and the home Grand Slam holds a special place in the now-29-year-old's tennis star's heart.

"It's truly the best, greatest feeling in the entire world," Keys told JWS last week. "I think there have been some of my most heartbreaking moments in front of a US Open crowd, but also some of my absolute most favorite, literally to the point of mid-match getting goosebumps."

Ahead of today's 2024 US Open kickoff, Keys commented on the power of the New York Slam's fans, saying, "The thing I've always loved about playing at the US Open is that, literally no matter how down and out you felt, the entire crowd was still there trying to get you through and push you through."

A chaotic 2024 sets up Keys's US Open appearance

The world No. 14 has had a rollercoaster 2024 season, missing the Australian Open due to injury before making solid finishes at WTA events in Miami, Madrid, and Strasbourg.

The Illinois product then suffered an injury at Wimbledon, withdrawing in the Round of 16 while in a winning position against eventual finalist Jasmine Paolini. "As devastating as that match against Jasmine was, it was also one of my favorite matches that I've played," she explained. "Just because I feel like we were both playing so well."

Her veteran perspective allowed Keys to calmly view the injury for what it was: a simple setback. "[Wimbledon] was really reassuring that I didn't do anything wrong," Keys said. "It wasn't this big thing that we had to worry about or manage. It was just really horrible timing."

"I've started to change my perspective on success and goals," she added. "At the end of every day, being able to say, 'Okay, did I accomplish my goal? If not, what were the lessons learned? How can I move forward with them?' I think that's honestly the best way to go about success in tennis."

Prioritizing health is vital to Keys's tennis career

The 2016 Rio Olympic semifinalist pulled out of the 2024 Paris Games in an effort to maintain her wellness and gear up for the season's final Slam — a decision she says was hard-won.

"It’s one of the greatest honors to be able to play for your country and play at an Olympics, and it was honestly one of my favorite tennis moments of my life," she said. "But I'm getting older — I've been on tour for a long time. They like to call me a veteran now, and I think you have to start shifting gears a little bit to prioritize the best schedule... to be able to maintain a high level and stay healthy."

At this stage in her career, Keys notes that every little thing matters, like putting nutrition and rest first in the run-up to another US Open while also partnering with supplement companies to boost her conditioning along the way.

"It's a lot about the details — we're constantly putting our bodies under insane amounts of stress and traveling," she said. "Being able to, like, literally not get a cold, something as small as that. I've been lucky to be able to partner with Thorne — that has been my absolute go-to — because if I can do all of the things right, I'm setting myself up for success.

"The other thing is prioritizing recovery, making sure that I have my whey protein, getting a good night's sleep, and being able to recover — those things are so important. Most people would think, 'Oh, it's about time in the gym and on the court.' That's obviously really important, but it's all of the little details that create the full picture."

Recognizing that pacing her seasons and listening to her body will help protect her health and, ultimately, her career, Keys is clear on her path forward. "At this point in my career, my biggest goal is I want to play tennis for as long as I want to play tennis," she said. "I don't want some outside force to be the reason that I have to step away from the game."

Decorated defender Tierna Davidson might be both the youngest and wisest veteran on the USWNT.

The Menlo Park, California native has been a fixture on the senior squad since 2018, picking up accolades during the team’s 2019 World Cup, 2021 Olympic bronze, and 2024 Olympic gold medal runs. Throughout her tenure, Davidson's played under three different USWNT coaches — four counting two-time interim manager Twila Kilgore — underwent multiple roster and tactical shifts, fought her way back from serious injury, and witnessed a generation of her teammates pass the baton to a young and hungry new class.

Given all that, it’s almost impossible to believe she’s only 25.

"[It] was so exciting to see all of these young players grow into themselves in this tournament and really express themselves on the field — to see the personalities, to see the styles of play, to see the chemistry building — when I was first on this team, I was just so focused on playing," Davidson told reporters last week during a promotional appearance at Raising Cane's Chicken Fingers in New York. "Being a little bit myopic about it, you don't really see those growth patterns — perhaps I was the one doing that growth — but to see some of the younger players have such a fantastic tournament experience, I think it bodes really well for the future of the team."

Davidson’s former myopathy is more than understandable. Six years ago, the then 20-year-old was the youngest player on former coach Jill Ellis’s 23-player World Cup roster. And with an average age of 28, more than half of that 2019 squad arrived in France with prior World Cup experience. Yet it was Davidson’s first major tournament at the senior level — and, ultimately, her first major tournament win.

Now closer in age to more recent additions like Trinity Rodman (22), Croix Bethune (23), and fellow Stanford Cardinal Naomi Girma (24) but with the same national team experience as players five to 10 years her senior, Davidson is able to serve as a bridge between the USWNTs of the past and today’s iteration. And it’s something she’s tapped into as she’s evolved her own style of play over the years.

"I've tried to take everything that I've learned from some of the older players and then also from myself over the past few years and commit that to my game," she said. "Playing with different players brings out new and exciting things in your game, and as I've made connections with some of the players on the field that I haven't gotten a chance to play with as much, different parts of my game come out."

Ushering in the USWNT's Emma Hayes Era

One person Davidson hadn’t played with much prior to the Olympics wasn’t exactly on the field, or at least not over the touch line. Current USWNT head coach Emma Hayes joined the USWNT in May from London’s Chelsea FC, bringing with her a shining record and high expectations, both from within US Soccer and from the greater public. As a player, Davidson approached the personnel shift with the same open-minded optimism she harnesses on the pitch.

"We all knew that she was a great coach — we'd seen what she had done with Chelsea and knew that she was going to be really great for our group," she said of Hayes. "But we weren't exactly sure, even just the basic things of how she wanted to run a training session or how she coached on the sideline. Those are the things that we had to build into and learn."

The fact that Hayes landed in the States some two months shy of the USWNT kicking off in France wasn’t lost on the team — or on their incoming manager. "Coming into the Olympics, it was something we all recognized and acknowledged, herself included," Davidson added. "I think that was so powerful to just get the elephant out of the room and say, ‘This is weird, it's not normal that you have a brand new coach coming in right before a major tournament, but we're going to commit to each other and we're going to commit to the process.’"

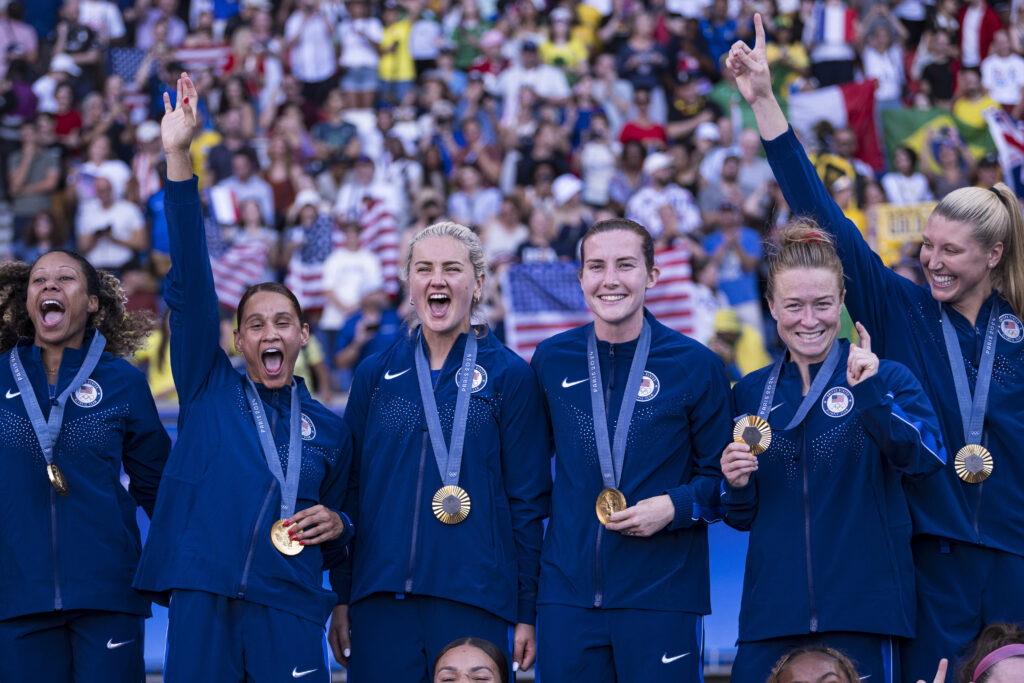

The commitment obviously paid off. The US walked away with the gold medal after going 6-0 on the tournament, greatly improving upon their mercurial 3-1-2 bronze medal performance in Tokyo. The Olympic success also worked to right the ship after the team’s Round of 16 exit from the 2023 World Cup — the USWNT’s earliest departure since the Cup’s introduction in 1991.

Even at the Olympics, Davidson says injury is part of the game

But the team’s Olympic victory didn’t come without setbacks, especially for Davidson. The center-back tore her ACL while training with her then-club team the Chicago Red Stars in 2022, failing to make the Australia-bound World Cup roster in 2023 before working her way back into the lineup over the past year. In France, Davidson left the USWNT’s second group stage match in the 44th minute after suffering a knee-to-knee collision with German player Jule Brand. The knock sidelined the regular starter for the following two games, with fellow defender Emily Sonnet taking over her position while she recovered.

"You wouldn't wish it upon anyone to get injured during a tournament, especially a tournament that you blink and it's over," the Gotham FC defender reflected. "It's just part of the game and it is what it is, [and] people are ready to step in and fill the role that needs to be filled."

As Davidson explained, her previous season-ending injury helped her maintain such a measured mindset under the Olympic lights, one that carried her through all the way to the finish line. "Unfortunately it's something that you agree to when you sign up to be a professional athlete: You agree to the uncertainty, you agree to the possibility of injury," she said matter of factly. "My story is not unique in that sense — people get injured, people get traded, choose to go to a new team, or get left off a roster. I think that that's what makes the moments of triumph so much sweeter."

"There are bits of it that only I will know and only my family will know, and that's why we have to celebrate these moments and appreciate these moments," she added. "Because for us as athletes, they're very fleeting, and there are a lot of darker moments that lead to these ones — [it’s] important for our growth as players and as people. So I wouldn't change it."

To overcome Olympic uncertainty, the USWNT turned to joy

From the first time they took the pitch in the South of France, any onlooker could tell there was something different about this US Women’s National Team. The tensions, miscommunications, and grimaces that hung over the last two major tournaments appeared to have dulled, passes looked more fluid, and goals were celebrated with more unbridled gusto.

While the pressure to take home the title and reclaim their previous spot at the top of the FIFA rankings was definitely there — the USWNT dropped to fifth place after the 2023 World Cup, the lowest they’ve sat since FIFA started ranking women’s teams — it didn’t seem to burden the players for the first time in years.

Perhaps all the recent change helped to simplify the team’s outlook heading into the Games. After all, for Davidson, change has been a constant.

"We had a relatively different roster and a lot of uncertainty with a new coaching staff coming in, so it's really a testament to our commitment to each other [that] we just all walked in and decided we were gonna do it whether it was perfect or not," she explained. "Understanding there were going to be bumps in the road and not expecting perfection from ourselves, not putting ourselves under that kind of unrealistic pressure… to just be okay with that and to be able to turn to each other if we needed. Everyone really bought into that."

After the final whistle blew at the gold medal game in Paris, NBC asked a visibly emotional Emma Hayes how she managed to get the USWNT, after all they’ve been through, to buy into a new coach’s philosophy so quickly and wholeheartedly.

"Just love," she responded. "I come from a place of wanting players to enjoy themselves."

The word "joy" permeated every interview that followed, from striker Mal Swanson’s postgame comments to captain Lindsey Horan, who, when asked when joy had returned to the squad, told reporters "To be perfectly honest, the past two months."

Davidson echoed their sentiment. "Each game that we play is a 90-minute game — in some cases 120 — but we have the same objective that we always do," she said of the team’s mentality under Hayes. "That really released us and allowed us to play with joy and play with each other as teammates but also as friends… This group got a taste of what it's like to win at the international level on a big stage, and I think everybody wants to be back there again."

Throughout the tournament, that joy spilled over into the team’s off-pitch endeavors. Social media posts of players putting the finishing touches on lego sculptures and jigsaw puzzles permeated the internet, while videos of them leading a particularly passionate singalong in the Team USA bus took on a life of their own.

"I mean I'm not one of the avid Cheetah Girls fans on the team but we do have a few," said Davidson when asked how "Strut" by the fictional Disney Channel teen pop group became the team’s Olympic anthem. "We were trying to decide what our new walkout song would be — like the last song we play before we leave the locker room for warm-ups — and a few different options were thrown out and that’s the one that raised the locker room to new levels."

For the USWNT, leveling up has never before looked so fun.

England and Arsenal forward Alessia Russo already knows how she wants to spend her time in the United States.

The team is preparing for a first-of-its-kind preseason tour, first playing the NWSL’s Washington Spirit on August 18th at Audi Field, before a friendly against longtime WSL rival Chelsea on August 25th. But Russo also has other plans for her time in Washington, DC.

"I'm excited to go to Chipotle — I love it there," she told Just Women’s Sports about a week before her team was scheduled to fly across the Atlantic. "They do actually have a couple in London, but they're really far out for me. So I'm looking forward to Chipotle."

Russo has already seen her football career take her to heights she only dreamed of as a kid, winning the European Championship in 2022 with England, making it to a World Cup final the following year, and signing with Arsenal in 2023 after a successful three years starring for Manchester United.

Russo's footballing journey first took her to the US in 2017, where she cut her teeth in NCAA soccer at the University of North Carolina alongside current Arsenal teammate Lotte Wubben-Moy. In a way, her team's trip to Washington, DC — about a four-hour drive from Chapel Hill — is a bit of a homecoming for the striker.

"I loved my time at college," said Russo. "I remember going out there quite young and naive, and I thought I'd kind of throw myself into this new environment and experience. I came out of it with best friends that I still speak to now all the time."

Even as sold out stands at Wembley have become commonplace for the 25-year-old Kent native — not to mention the increasingly enormous crowds at London's Emirates Stadium where Arsenal Women will be playing 11 home games this season — Russo's memories of Chapel Hill are more akin to the average college student.

"We used to have our pre-games all the time at Panera," she recalls. "Everyone used to think like, 'Why are we going to Panera again?' But Lotte [Wubben-Moy] and I used to love it, so I'm sure we'll take a visit back there."

While Arsenal’s preseason tour will allow Russo plenty of time to relive her glory days, it will also act as prep for the upcoming WSL season, as well as a way to reach fans that might not otherwise ever get to see their favorite players in person. The club has leaned into those particular opportunities throughout the 2024 offseason, already completing a short tour of Australia.

Russo has cherished the chance to play in front of fans across the globe, but with a tight international calendar and mounting club workload, she’s had to be mindful about getting rest on her precious off-days.

"I think you really need to make the most of it when you do get time to fully switch off," she said. "[It's] something that when I was a little bit younger I probably wasn't as good at, but as I get older, it's knowing your body a bit more, knowing what works for you."

She enjoys the rare warm weather holiday, and Russo went on to note the support she has gotten from both the Arsenal and England training staffs, and how load management — especially during preseason — can be a key factor to achieving individual and team goals.

Their test against an NWSL team currently sitting third in the league standings will also be an important step in Arsenal’s preseason plans, as well as a challenge that draws specifically on Russo’s time at North Carolina. The NWSL is known for high transition-style play, moving the ball quickly and hurting their opponent on the counter.

The Spirit have taken that ethos and evolved it this season, creating a sturdy midfield that can retain possession as well as push back on the wings with former Barcelona manager Jonatan Giraldez taking full control of the squad.

"I think it's going to be a really tough game, and we all know that," Russo added. "Also, they're in their season, so they're going to be firing, they're going to be on form."

But should the match open up, Russo will be ready: "Going to the states, I developed a different side of the game in terms of strength and power and physicality, because in order to fit into the game and into college football, you needed to be strong."

"I just had to kind of catch my body up with where I needed it to be," she continued. "And it's still something that you work on now, but UNC was kind of the starting point for all of that."

Arsenal will need to rely on all of Russo’s past experiences this season, as the club reshapes its attack following the high-profile exit of superstar forward Vivianne Miedema, who signed with perennial title contender Manchester City earlier this offseason. And while Miedema’s playing time had dwindled at Arsenal after returning from injury, the team still has serious offensive connections to mend should they want to better their 2023-24 third-place finish in the WSL. According to Russo, diversity will play a major role in hammering out Arsenal's reformation.

"I think we've grown a lot as a team and we've reflected a lot after last season," said Russo. "Ultimately, a club like Arsenal, we want to be winning trophies and we know that we have the talent to do so — in the changing room and with all our staff.

"I think we have so many special players on the ball, off the ball, wingers and 10s that possess so many different qualities even between them — one winger might like to do, the other is completely opposite. That makes it really cool and unpredictable."

Russo describes herself as a forward-thinking player who loves to score goals but can also embody the off-the-ball roles of a No. 9, with an emphasis on pressing triggers when the team is out of possession. Execution in attacking spaces could make all the difference for a club looking to battle teams like Chelsea and Manchester City for domestic titles, as well enter back into the apex of European competition with their impending UEFA Champions League campaign.

Arsenal is also prepared to continue to push the sport forward, capitalizing on a global movement that’s propelled the rise of women’s football in the US, Europe, and beyond. Russo noted that while the talent on the pitch has always been there, but she feels lucky to be part of a generation that's bringing women’s sport into the spotlight.

"[Fans are] genuinely wanting to see the game grow, and they're actual fans of women's football," she said. "To play in those kinds of stadiums — whether that's in England, in Australia, in the US — women's football now is never questioned, we have our fan bases and we're getting to the stages that we deserve."

For Russo, the path forward is clear: win trophies with Arsenal, carry that momentum into the 2025 Euros, and excel in every international and club tournament beyond that — all while never forgetting her sense of gratitude, no matter how high her star ascends.

"People have a genuine connection to following these journeys and these stories," she said. "I feel very privileged to be in that kind of position, and hopefully long may it continue."

In the latest episode of Just Women's Sports' 1v1 With Kelley O'Hara, Gotham FC and USWNT star Rose Lavelle joins Olympic gold medalist and retired USWNT star Kelley O'Hara for a one-on-one conversation about the upcoming Paris Olympics.

We hear from Lavelle about her first impressions of new USWNT coach Emma Hayes, her international competition journey so far, and what it's like being one of the veterans on this roster.

Subscribe to Just Women's Sports on YouTube to never miss an episode.

In the latest episode of Just Women's Sports' 1v1 With Kelley O'Hara, Gotham FC and USWNT defender Emily Sonnett joins Olympic gold medalist and retired USWNT star Kelley O'Hara for a one-on-one conversation about the upcoming Paris Olympics.

We hear from Sonnett about her first impressions of new USWNT coach Emma Hayes, her international competition journey so far, and what advice from past USWNT players she's planning to take into the 2024 Summer Games.

Subscribe to Just Women's Sports on YouTube to never miss an episode.

In the latest episode of Just Women's Sports' 1v1 With Kelley O'Hara, San Diego Wave and USWNT star Jaedyn Shaw joins two-time World Cup champion and Olympic gold medalist Kelley O'Hara for a one-on-one conversation about the upcoming Paris Olympics.

We hear from the 19-year-old Wave FC phenom about her first impressions of new USWNT coach Emma Hayes, her experience with international competition at this point in her young career, and how she's preparing to take on the 2024 Summer Games.

Subscribe to Just Women's Sports on YouTube to never miss an episode.

Phoenix Mercury guard Kahleah Copper has been working toward this year's WNBA All-Star Weekend for a long time.

2024 won't be Copper's first trip to the All-Star Game — in fact, she's been an All-Star for four consecutive seasons. This weekend also won't be Copper's greatest individual achievement to date. Afterall, it's tough to beat winning Finals MVP as part of the 2021 WNBA Champion Chicago Sky. And this year isn't even Copper's first time playing the All-Star Game in her home arena; that was in Chicago in 2022.

But this will be Copper's first All-Star Weekend as an Olympian, a title she's been striving for since the moment the Tokyo Games ended in August 2021. Back then, the 29-year-old had been one of Team USA's final roster cuts prior to the Olympics. And from that day forward, she made it her mission to channel her disappointment into becoming an indispensable part of the 2024 Paris Olympic squad.

"I wouldn't change my process for anything," she told Just Women's Sports earlier this week as she prepared to join the national team at training camp in Phoenix. "I'm super grateful for it, it has definitely prepared me. It's a testament to my work ethic, and me just really being persistent about what it is that I want."

A proud product of North Philadelphia, Copper has always been big on manifesting, speaking her intentions confidently into the universe and never shying away from ambitions no matter how far-fetched they sounded.

"It's important to set goals, manifest those things, talk about it," she said. "Because the more you speak it, you speak it into existence."

She also displays those goals on her refrigerator at home, forcing herself to keep them front of mind every day. The day she was named to the Olympic roster, ESPN’s Holly Rowe posted one of these visual reminders to social media: A 2021 photo showing Copper wearing a Team USA t-shirt over her Chicago Sky warmups, smiling at the camera while holding up the homemade gold medal slung around her neck.

"Kahleah Copper put out [the] photo on the left in Aug. 2021 and manifested that she WOULD be an Olympian," Rowe’s caption read. "Today she made team USA. Dreams to reality."

Copper turns her focus to Team USA

With one dream realized, Copper is aware that the job isn't finished, as USA women's basketball is aiming to win a historic eighth-straight Olympic gold medal in Paris this summer. That path doesn't technically begin with All-Star Weekend — where Team USA will take on Team WNBA in a crucial tune-up game — but the trial run could make a difference when the team touches down in Europe next week.

"It's serious, because other countries, they spend a lot of time together, so their chemistry is great," Copper said of her Olympic competition. "We don't get that, we don't have that much time together. Just putting all the great players together is not enough. It's gonna take a lot more than that."

With a laugh, Copper acknowledged that Team USA’s task at hand could lightly dampen the occasionally raucous All-Star festivities ("Balance!" was an oft-repeated word). But it's a cost she and her national team colleagues are more than willing to pay if it helps them come out on top in Paris.

Of course, Copper — along with club teammates Diana Taurasi and Brittney Griner — will be enjoying home-court advantage when the All-Star Game tips off inside Phoenix’s Footprint Center on Saturday, a factor that might put them slightly more at ease.

A "damn near perfect" new WNBA team

Copper made the move to the Mercury just this season after establishing herself as a respected star in Chicago. What she joined was a work in progress, one of a number of key 2024 signings under first-time head coach Nate Tibbetts. Having played for the Sky since 2017, Copper wasn’t exactly sure what to expect of the transition. But any positive manifestations she put out about her new team seemed to have done the trick.

"I said I would never go to the West Coast, I could never go that far from home," she said. "But I didn't know that this organization was what it was: Super professional, really taking care of everything. It's damn near perfect."

Copper herself has been damn near perfect, shooting 45% from the field while leading sixth-place Phoenix to a 13-12 record on the season. She’s also averaging a career-high 23.2 points per game, second highest in the league behind soon-to-be six-time WNBA All-Star A’ja Wilson’s 27.2 points per game. It’s not lost on Copper that she’s playing in front of packed houses, with the Mercury accounting for some of the W’s biggest crowds throughout its 28-year run.

"Here in Phoenix, our fans are amazing," Copper said. "They show up every single night."

Copper's All-Star home-court advantage

All-Star Weekend presents Copper even more opportunities to connect with her new city, including by making an appearance at American Express's interactive fan experience at WNBA Live 2024. As part of the activation, Copper recorded a few short stories about growing up a basketball fan, describing the posters of Candace Parker, Seimone Augustus, and Ivory Latta she had as a child, and how she dreamed of joining her idols as a professional basketball player.

The Rutgers grad said she was excited about connecting with Phoenix fans on their level, rooting herself in a shared love of the sport even as she moves from watching the WNBA on TV to becoming one of its brightest stars. The message is clear: If you want something bad enough, and you work for it hard enough, just about anything is possible.

But for all of Copper's personal manifestations, she's never lost sight of the most important thing: winning. And she won't stop grinding until she's posing for the cameras in Paris, holding up a real Olympic gold medal.

"When winning comes, the other stuff will come," she said. "The individual sh*t will come."